David Trautrimas

David Trautrimas’s inclination towards experimentation with new media has inspired his use of a broad range of integrative techniques from creation of laser-etched acrylic sculptures to digitally rendered photographic prints. His experience as a Smokestack Analog Print Residency participant became an opportunity to further expand into unfamiliar media territory with a print process not only unfamiliar to him but also to Laine Groeneweg, Smokestack’s analog printmaker and residency collaborator. Cyanotype is a camera-less photographic technique involving the coating of paper with a light-sensitive solution to expose the form of an object or obstruction onto the surface, but through David’s residency, such a process was expanded to produce a breadth of print works very much outside of the realm of traditional photography.

-

In these first days of experimentation in the studio, we started to see what we could do with cyanotype and what particulars of material and process were involved.

-

Experimentation was ongoing saga throughout the residence. This came to involve a number of exposure and development timing tests to see what would be needed to actualize the imagery the way we wanted. In the case of "Aphasia", we were looking for a value diagram between the 2nd and 1st panel (the middle and shallow end of the pool),

-

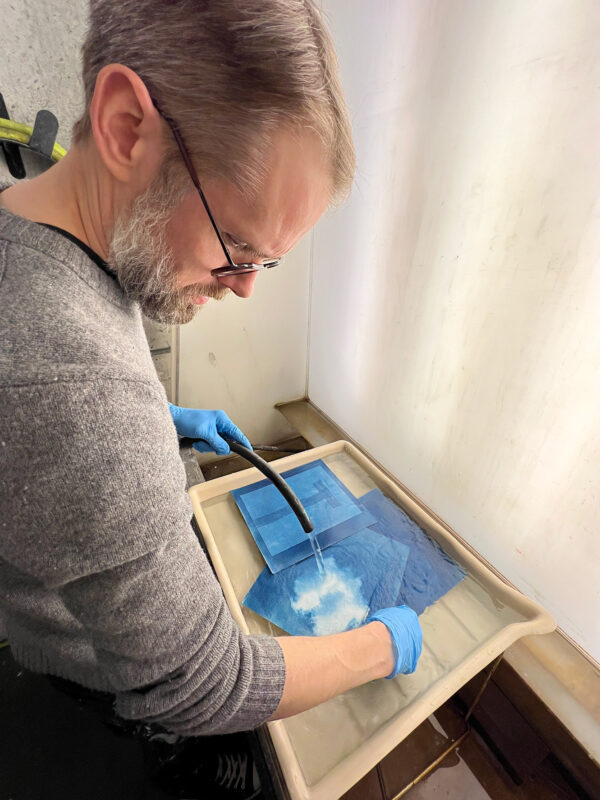

We came to find different ways of coating the paper with emulsion chemicals such as dipping & 'squeegeing'. These early experiments didn't come to fruition as expected, but valuable learning results nonetheless!

-

Paper was coated with emulsion chemicals that needed to be mixed in new batches periodically throughout the coating process.

-

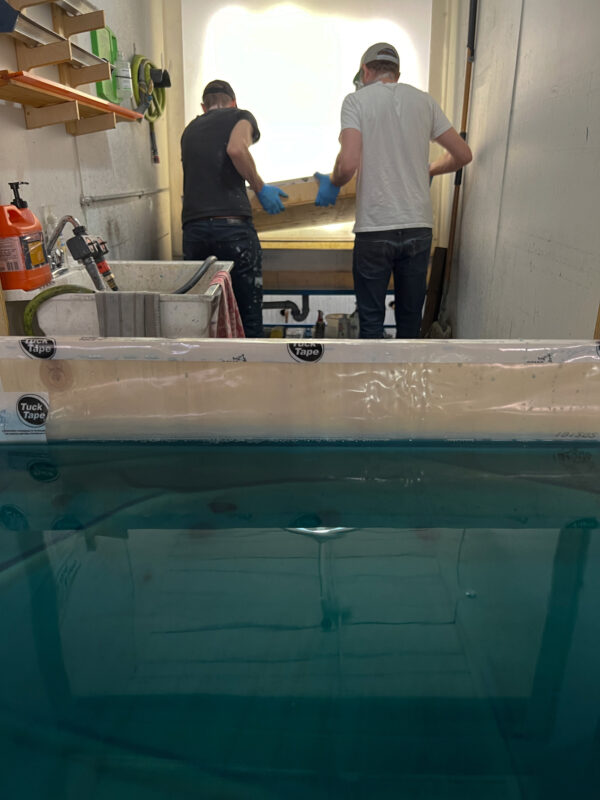

The coating stations varied in size and setup as needed based on the varying size of the artworks. Here we're preparing the coating station for one of the full sized sheets of "Aphasia" - largest single works produced in the residency.

-

Spreading the cyanotype emulsion on a large sheet of paper was a job for two!

-

Papers were laid out on silkscreen meshes as soon as they were coated with emulsion to best ensure they dry flatter and more evenly. Once dried, they were then ready to be exposed.

-

Following exposure, works were developed using a vinegar solution to 'fix' the image. Time for more experimentation! Test strips of the smaller pieces were used to prep the vinegar developer before moving onto development of the larger sized prints.

-

After development, it is essential to rinse the prints multiple times to make sure all chemicals used in its development are removed. Set-up of a large water bath for soaking proved a good technique as an initial rinse.

-

Further rinsing with running water ensured all chemicals were removed.

-

In addition to coating, development, and rinsing technicalities, the kind of paper used played a large part in how successful the cyanotype prints resolved. We experimented with many different types of paper which contributed to vastly different results.

-

With a better grasp on the process, we were confident to move on to the larger works. Laine brings one of the "Aphasia" panels here into the vinegar developer bath.

-

The vinegar in the development bath needed to be agitated to ensure a consistent development of the exposed cyanotype. Gently rocking the entire development tray became a good strategy, particularly for the larger pieces.

-

Dumping out the rinse water for the larger works was a two-man job.

-

After the final wash bath, prints were left on an angle so that moisture can drain off before being laid on on newsprint to fully dry. A great time to admire the finished results!

A few words with David Trautrimas...

-

Smokestack Gallery Director, Tara Westermann (TW): Starting right into media particulars, how did you come to focus your residency on work in cyanotype?

David Trautrimas (DT): I thought about working with silkscreen initially, but there were mid-tones in one of the larger pieces I wanted to create, "Aphasia", that wouldn’t translate with silkscreen and so we chose to work in cyanotype for that one - once we figured it out. On a whim another day, we decided to expose one of the other pieces as a cyanotype and then it clicked. I realized that screen wasn’t the right medium at all and that cyanotype was instead what we were going to use.

-

TW: So you had a pretty clear idea of the imagery you were going to actualize before the start of your residency?

DT: For the two larger works in the series, "Aphasia" and "Choir Practice", yes. I knew there would be some additional smaller pieces that I wanted to make as well which were resolved through the residency but was a lot of preliminary work done with imagery development before we started in the studio. The residency came to be primarily focused on technical growth and exploration rather than concept and content.

-

TW: You’ve had experience with a range of photo and print media processes throughout your artistic practice. How did you find the cyanotype process similar or different?

DT: In a lot of respects, it felt very familiar. I spent a lot of time at OCAD during my student days and afterwards working in dark rooms using mostly black & white photographic processes and at the end of the day, cyanotype is a photographic process itself: you have light, emulsion, a substrate and a developer. So it shares those fundamental aspects, though when it comes down to the “nitty-gritty”, it is quite different. It was very easy to get an okay result, but very challenging to get a reproducible, precise result. I believe that may be a lack of professional context or resources around cyanotype. A lot of the information we were finding seemed geared towards hobbyists and what Laine and I were trying to do presented a demand for precision and repeatability (especially when it comes to editioning) that saw us running up against a lot of technical challenges. A lot of trial and error. There were times that we’d watch a print just dissolve and bleach out in front of our eyes 10 minutes after we thought we figured something out. Where there would be ample resources for the production of other kinds of processes, we felt like we were really having to build our own recipe for this.

-

TW: You’ve worked with Laine a number of times over the years, but with print disciplines that Laine had more developed experience with. Seeing as how neither you or Laine had experience with cyanotype before, how did this collaboration play out?

DT: Well, it felt like we both went in as if we were typing with mittens on - just figuring out the location of one key at a time to find some fluency. Laine of course brought a lot of experience handling wet paper which is a big part of the cyanotype process, though we discovered that identical papers reacted very differently through cyanotype as they would through etching even though both similarly involve a multiple-soaking process.

-

TW: So truly a collaboration at the most fundamental level.

DT: Oh absolutely. And there was a point early on that I had my doubts whether we could actually achieve the results we were looking for with cyanotype, but Laine’s energy and optimism really carried us through at those crucial moments. Just one more test…And as it turned out within a day or two we had figured out those first major hurdles that moved us forward.

-

TW: The variation of visual and physical forms within this body of work really demonstrates your drive to expand and push the medium seemingly to its limits. Was this the intention?

DT: The intent at first was to just try cyanotype for the large pool triptych but it really became the gateway drug with the process eventually taking over the whole body of work, and as much as it came with its measures of unpredictability, we came to find it quite flexible. In getting into the process I realized how much can be done with it. The milk carton piece, "D34+|-| IVII 1K", for example, was envisioned initially to be printed as 2-dimensional works, but the more I looked at it and the more we experimented with cyanotype, the more I wanted to make them actual objects and I was interested in the challenge. The fun of that was in trying to push the medium; “can we actually do it?”. The trial and error ended up working really well and I do envision doing more of this kind of sculptural cyanotype work in the future.

-

TW: With regards to imagery content, in your practice there’s an explorative through-line with cultural phenomena and every-day spaces & objects. What aspects in particular have you been looking towards or considering with this series?

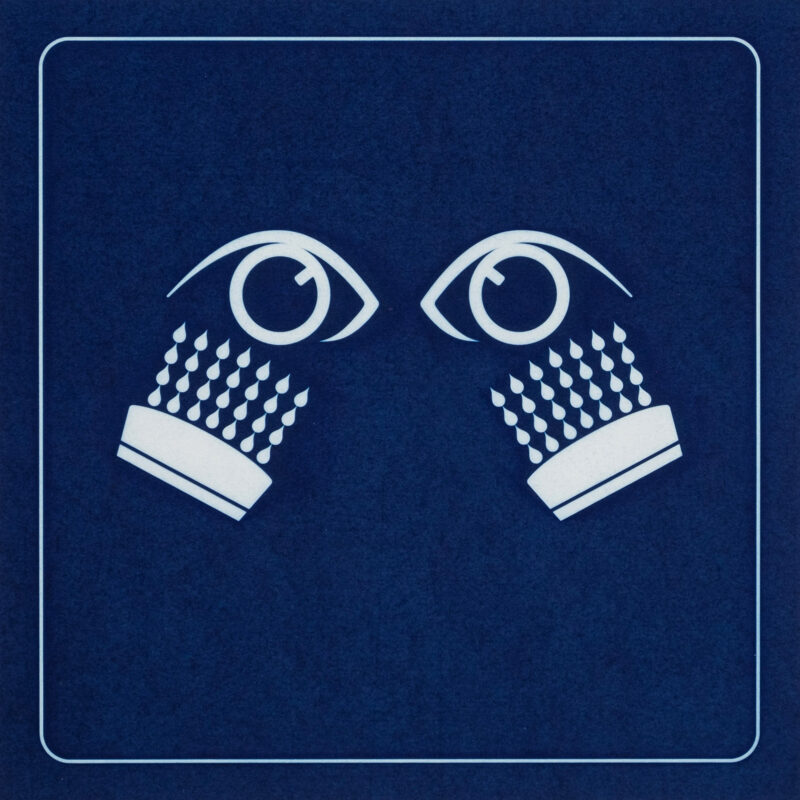

DT: In some senses this body of work is a departure; still looking at narrative themes of the human experience but not so much the domestic or every-day. This series is really focused on more global human themes. I was inspired by a term, Vale of Tears, which is a tenet that underpins a lot of religions – from Christianity to eastern philosophy – that asserts life is suffering and that it’s only in the afterlife that we find deliverance from this suffering. I’m not necessarily an ardent believer in the paradise of an afterlife but through lived experience I can say that there is suffering and there are moments of deliverance. I was interested in creating a body of work that spoke to these global themes but also had very personal elements and narratives underpinning them.

-

TW: How does the title of the exhibition, Lengths, reflect these themes?

DT: I rarely rely on one word to convey something, but it seemed to fit all of the works (directly, conceptually, metaphorically) and how they’re positioned within so many universal narratives of suffering and its counterpoint. The lengths we go to avoid suffering, the lengths we go to find peace, the literal lengths to swim in a pool as a form of meditation, the lengths of distance ancestors physically have travelled to flee from trauma.

-

TW: The lengths of survival.

DT: Exactly.

-

David Trautrimas - Smokestack Analog Print Residency, 2024

-

-

David Trautrimas – D34+I-I IVII1K

- Cyanotype sculpture

- Edition of 12

- 3" x 3" x 6"

- 2024

$500.00

-

David Trautrimas – Aphasia

-

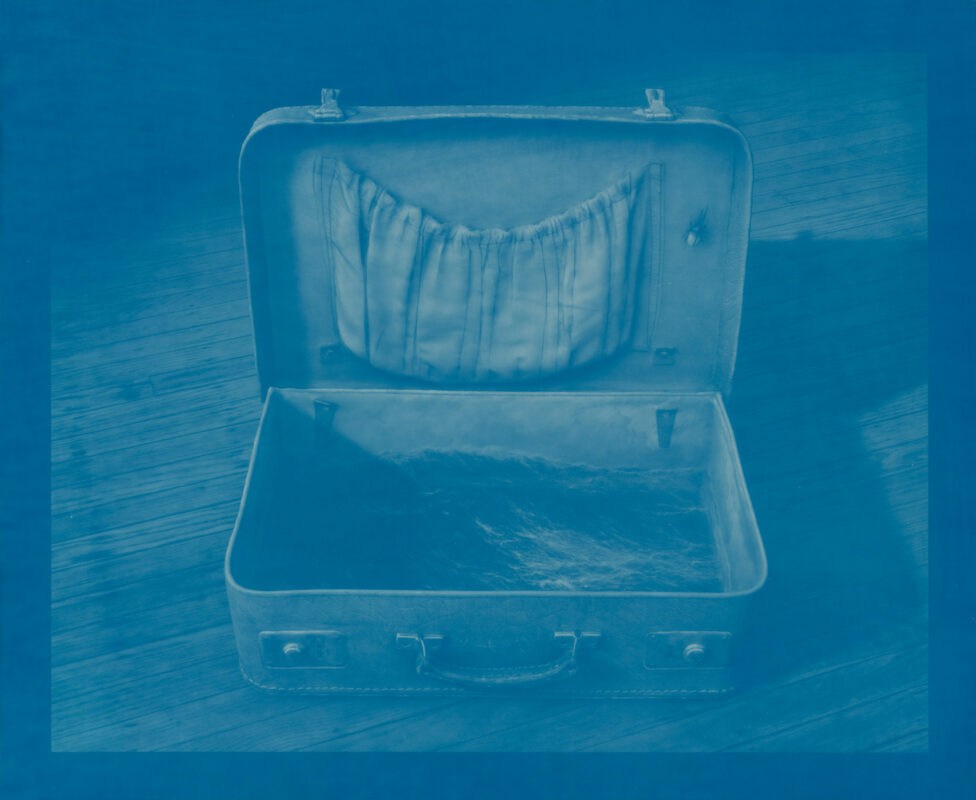

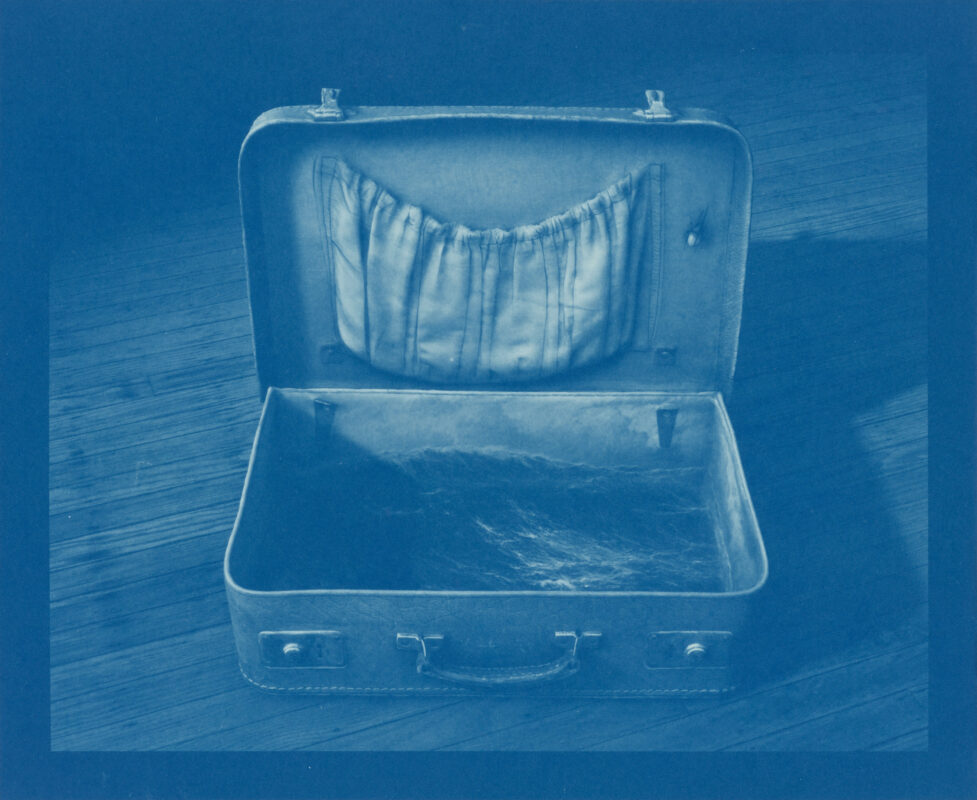

David Trautrimas – Anywhere Familiar is a Place on Earth, version 1

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 4

- 14" x 18"

- 2024

🔴

-

David Trautrimas – Anywhere Familiar is a Place on Earth, version 2

- Cyanotype on matboard

- Edition of 4

- 14" x 18"

- 2024

$600.00

-

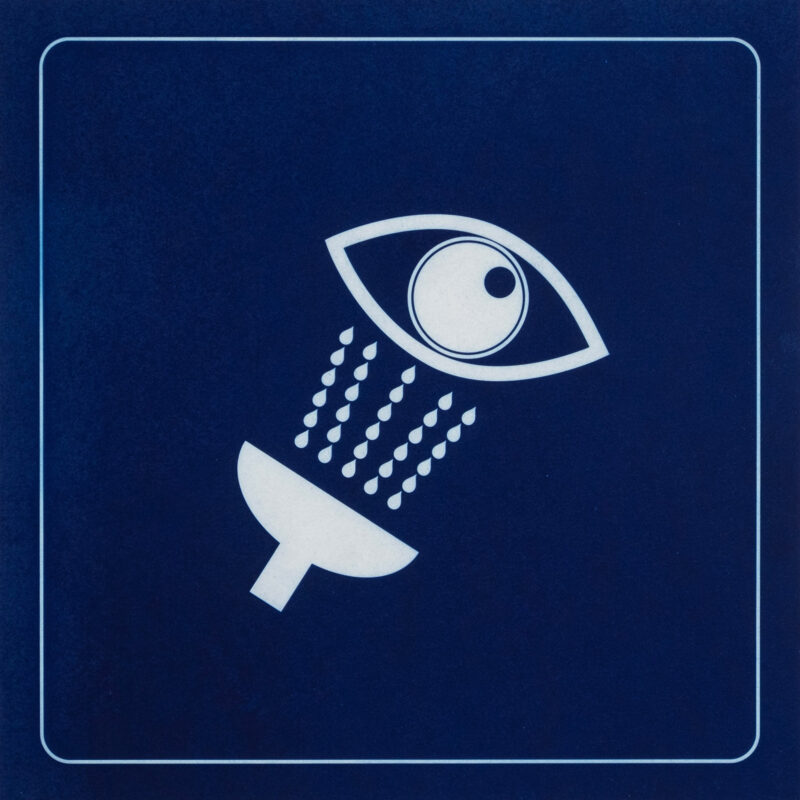

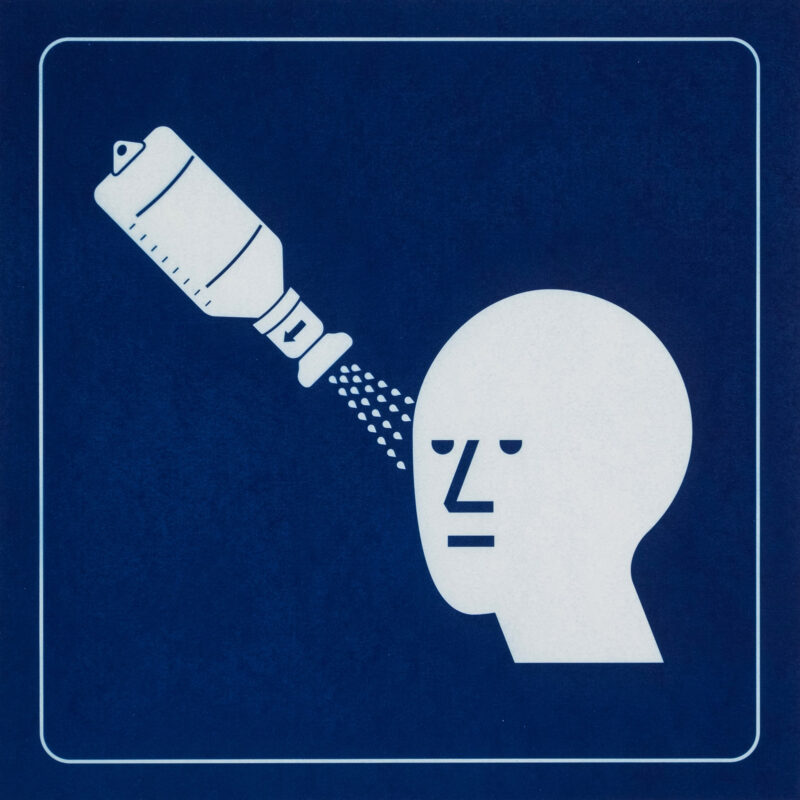

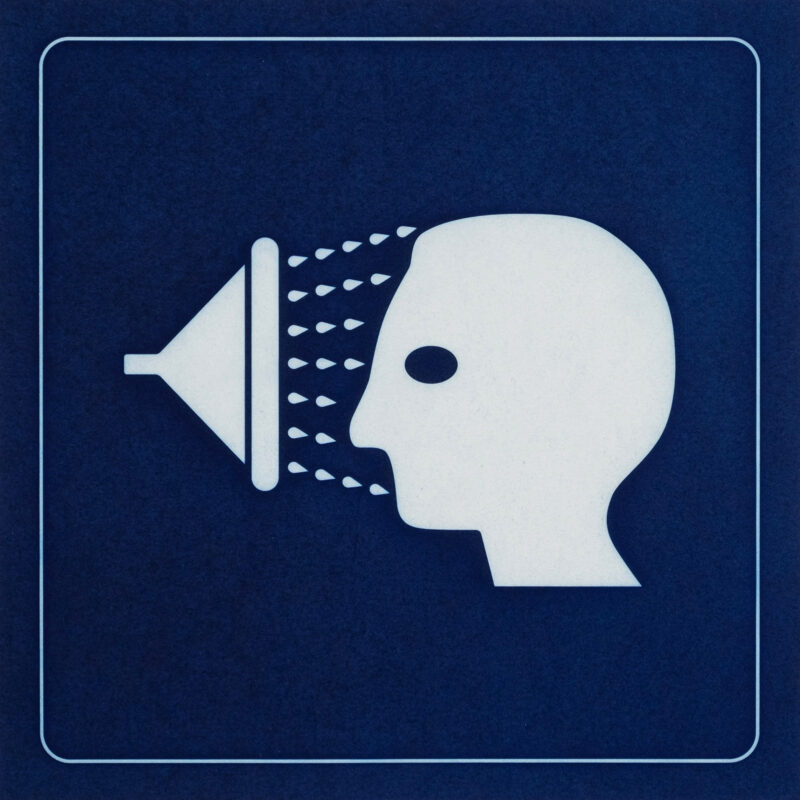

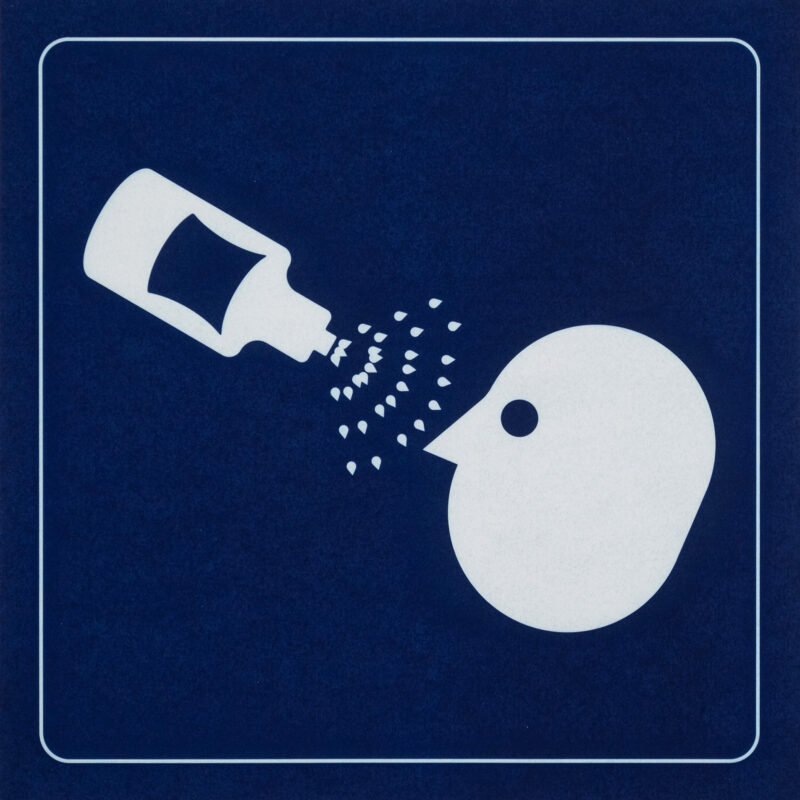

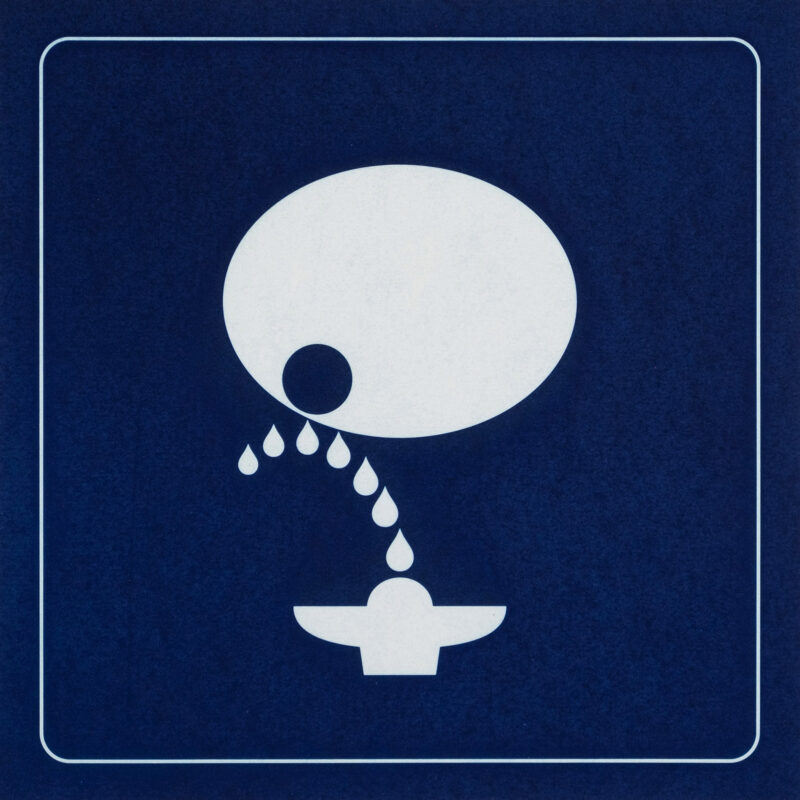

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice I

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice II

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice III

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice IV

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice V

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice VI

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice VII

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice VIII

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice IX

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice X

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XI

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XII

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XIII

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XIV

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XV

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XVI

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XVII

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XVIII

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XIX

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XX

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXI

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXII

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXIII

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXIV

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXV

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXVI

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXVII

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXVIII

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXIX

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXX

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXXI

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXXII

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXXIII

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXXIV

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXXV

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXXVI

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXXVII

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXXVIII

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

-

David Trautrimas – Choir Practice XXXIX

- Cyanotype

- Edition of 3

- 9" x 9"

- 2024

$350.00

This project was made possible with support from: